1. Why did the American and French armies come to our area in 1781, the seventh year of the Revolutionary War?

In 1780 the French King sent General Rochambeau and his army to America to assist Washington in his fight against the British. One year later, in July, 1781, Washington and Rochambeau brought their armies to our area, which Washington chose because of its proximity to British forces in New York. With the help of the French, Washington hoped to drive the British from Manhattan. Defeating the British in New York would be the knock-out blow that Washington needed to win the war. He knew that after 1781, French assistance would come to an end and that 1781 was America’s last chance.

2. Were the American army and the French army camped in Dobbs Ferry?

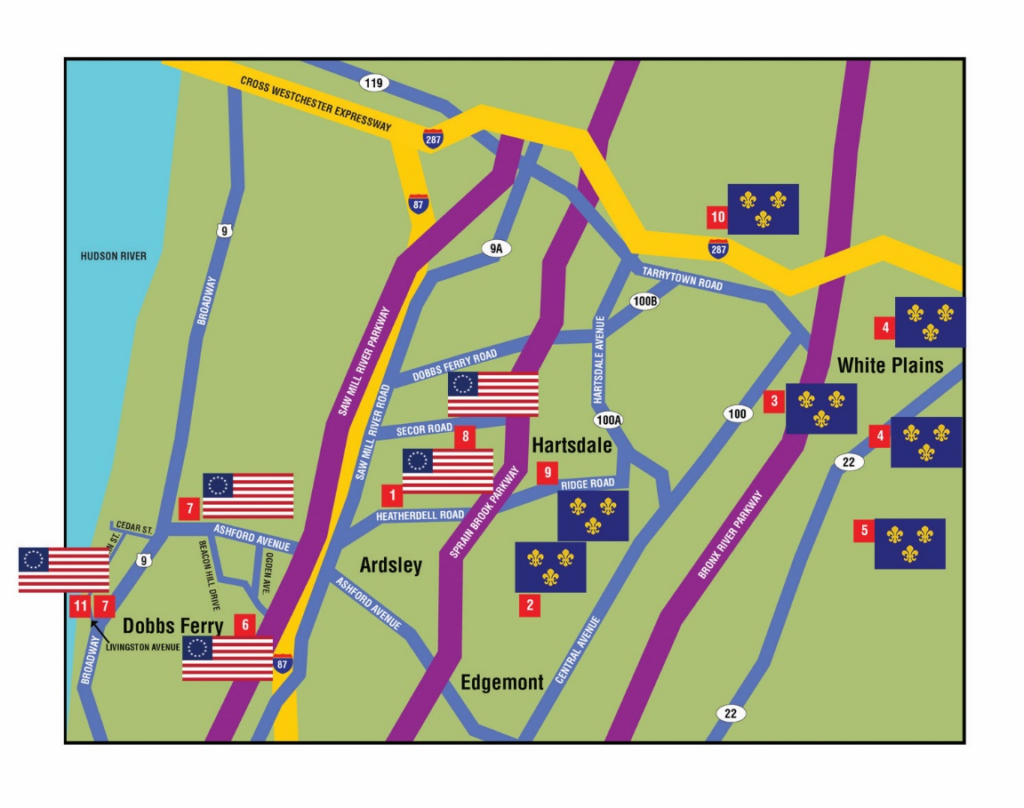

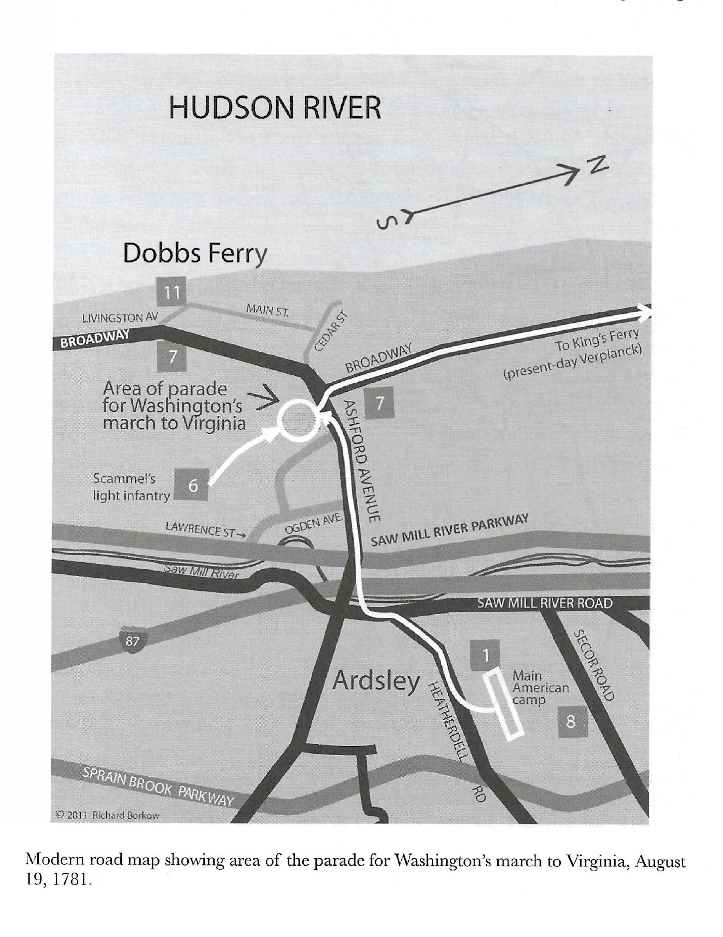

Washington had set up the camps of the two armies so that the American army was on the west side of the Sprain Brook and the French army on the east side. The American army was in present-day Dobbs Ferry and Ardsley, with Washington’s HQ in present-day Hartsdale. The French army was in present-day Hartsdale, Scarsdale, and White Plains.

3. Why did Washington decide to march the armies from Westchester to

Virginia?

Attempts to scout out British vulnerabilities showed that the British defenses were very strong on Manhattan and that it would be exceedingly difficult to drive them from New York. Then on August 14, a letter was received from French Admiral de Grasse in the West Indies stating that

he was planning to bring his powerful fleet to the Chesapeake Bay. De Grasse proposed that the American and French armies leave their encampment in Westchester in order to join him in the Chesapeake region and strike at British General Lord Cornwallis in Virginia.

Washington decided to follow this plan and bring the two armies to Virginia. There were numerous parts of this risky plan that would have to work perfectly for the plan to succeed. Washington would have to leave the Hudson Highlands and West Point with minimal defenses. He would have to undertake an arduous march of more than 400 miles with unpaid men. If Clinton understood the plan, he could attack the American and French en route or move reinforcements to Cornwallis. With unreliable communications, Washington might not know whether or not de Grasse had defeated the British fleet or even whether the French fleet had arrived in the Chesapeake. Suppose the British fleet did prevail over de Grasse and controlled the Chesapeake Bay. Then the tables could be turned and Washington and Rochambeau rather than Cornwallis, might find themselves in a trap. Because the defeat of Cornwallis might be the knock-out blow that Washington so desperately needed, he decided to march south despite the many risks.

4. Did the American army cross the Hudson at Dobbs Ferry?

A portion of the army did, but not the main army. On August 18, an advance party under Brig. Gen. Moses Hazen departed from the encampment and crossed the Hudson at Dobbs Ferry to set up a camp at Chatham, N.J. This was part of an elaborate subterfuge to convince British General Clinton in Manhattan that his forces in New York would be put under siege and to hide the true purpose of the allied forces, the march to Virginia. The main army did not cross at Dobbs Ferry and instead crossed the river 20 miles north at King’s Ferry (present-day Verplanck).

‘Danger and Deception at Dobbs Ferry’ Artist: Keith Rocco

Detail from NPS interpretive panel

installed at the Dobbs Ferry waterfront July 4, 2018

5. Did the French and American armies depart from Dobbs Ferry together to

march to Virginia?

The American army left its camps in Dobbs Ferry and Ardsley on Sunday, August 19, to begin the march to Virginia. Under the officers’ commands, the soldiers held a parade for the march in the area of Ashford Avenue and Broadway in present-day Dobbs Ferry before turning north onto Broadway. In 18 th century military parlance a ‘parade’ meant an assemblage of the troops, and occurred at the start of any major movement of the army. Therefore, Broadway and Ashford Avenue mark the starting point of the American army’s march to Virginia. After travelling 20 miles north along Broadway (then known as the river road), the Americans reached the Hudson crossing point at King’s Ferry (present-day Verplanck). This northern crossing point was chosen so the troops would be less at risk of an attack from British warships coming from their base in New York Harbor while they were crossing the Hudson.

The main French army also began the march to Virginia on August 19 after breaking camp in Hartsdale, Scarsdale, and White Plains. (Small French contingents departed on Aug. 18 and 20.) However, the French troops did not march to Dobbs Ferry and took an interior route rather than traveling along the river. They marched north from their camps to Pines Bridge and then west to Peekskill and from there, to King’s Ferry.

After the Americans and French crossed the Hudson, the allied armies marched south along

separate but parallel routes.

6. What was the route of the march to Virginia and how long was the march?

The map below shows the march from Dobbs Ferry to Yorktown. It includes

1) the French march prior to arrival at the side-by-side encampment with Washington’s forces

in Westchester,

2) Cornwallis’s movements prior to arriving at Yorktown, and

3) French naval movements that were essential to enable the siege of Yorktown.

The American and French armies traveled more than 400 miles from their Westchester encampment to Virginia. Many of the troops were transported by boat across the Chesapeake Bay from Head of Elk, Maryland, to Williamsburg, Va. (Williamsburg served as a staging area for

the siege of Yorktown.)

National Park Service: American Revolution at a Glance, 2001

7. How important were the French in the victory?

It is difficult to imagine how the Revolutionary War could have been won without the assistance of the French. Before the Battle of Yorktown, the French fleet, under Admiral de Grasse, defeated the British fleet at the Battle of the Capes on September 5. As a result of the defeat of the British navy, Cornwallis’s opportunities to escape by sea from Yorktown virtually disappeared. Not a single American fought in the Battle of the Capes, yet that battle, arguably more than any other, determined the outcome of the Revolutionary War and the eventual American victory. Also, French siege guns, brought to Yorktown by French Admiral de Barras from Rhode Island, were essential for the success of the siege, which began on Oct. 6, 1781. Additionally, American forces were supplemented by a large number of French troops, 3,000 of whom arrived with Admiral de Grasse. At the Battle of Yorktown, 6,500 American troops and 7,800 French troops laid siege to 7,200 British and Hessian troops.

8. Why was the Battle of Yorktown important?

Cornwallis and his army surrendered on October 19, 1781, two months to the day following the departure of the American army from Dobbs Ferry. Cornwallis’s surrender shocked the British Parliament and resulted in a vote of no confidence. A new government was formed which accepted the independence of the United States. Negotiations were started in late spring 1782 and led to uncontested independence for the United States and very favorable peace terms for the young republic.

9. Why are these important events that occurred in our village so little

known?

Historical accounts that describe the events that occurred at the American encampment of the summer of 1781 often take no note of the locations where these events took place. Dobbs Ferry was the starting point of Washington’s march to Virginia (see question #5) but that fact is often missing in these accounts. One possible explanation for this lack of recognition is that the area at that time was generally referred to as Phillipsburg, which was a large expanse. One might guess that authors of the many books on the topic did not have access to maps of Phillipsburg in order to nail down the present-day locations, particularly in the pre-Internet era. Many simply give the location of the encampment and start of the march as ‘north of New York’.

In fact in 1781 ‘Dobbs Ferry’ was a commonly used place name that referred to the vicinity of the ferry landing, though there was no incorporated village. George Washington wrote ‘near Dobbs Ferry’ as his location when he wrote letters and documents from his headquarters at the Appleby farm house, on the grounds of the present-day WFAS radio on Secor Road in Hartsdale.

The lack of consistent recognition of Dobbs Ferry’s role is one of the reasons why the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society in concert with the Village of Dobbs Ferry has organized an annual public commemoration of the departure of Washington’s army on August 19, 1781, to make this event better known. There are also two books written by former trustees of the historical society that explain the story of the encampment. They are George Washington’s Westchester Gamble by Richard Borkow and George Washington at “HeadQuarters, Dobbs Ferry” by Mary Sudman Donovan, both available in the Westchester Library System.

Author: Linda Borkow, Consultant: Richard Borkow

References

Richard Borkow, George Washington’s Westchester Gamble, The History Press, 2011

Washington’s March to Yorktown (map),

https://www.villagehistorian.org/Documents/EncampmentAlliedArmies15slides0001.pdf

Interview with Earl Warren Professor of History at Brandeis University, David Hackett Fischer

Fischer, David Hackett. The Seventh Year of the Revolutionary War, The Encampment of the American and French armies at Dobbs Ferry and neighboring localities, July and August 1781, interview conducted by Richard Borkow, May 24, 2009. YouTube, uploaded by VillageHistorian,

Nov 5, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxX0Kzfyeyk

Interview with Thomas Fleming at The Mead House, Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., author of Liberty: The American Revolution and many acclaimed books about the Revolutionary War

Fleming, Thomas J. The Washington-Rochambeau Encampment on the Hudson River in Lower Westchester, July and August 1781, interview conducted by Richard Borkow, June 7, 2009.

YouTube, uploaded by VillageHistorian, Jan 26, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jysQ0zbxVJI